I hope that with time the number of articles will grow. If can you think of a subject which needs addressing and has not been covered much elsewhere on travel to Poland, ancestral travel and genealogy feel free to let me know, you can find my email address in the 'Contact Us' section of this web site. Click on the title below to move to each article.

Planning a Successful Ancestral Journey to Poland

Cemetery Research

Planning a successful ancestral journey to Poland

This article appeared for the first time in the Winter 2009 issue of the Rodziny, a quarterly published by the Polish Genealogical Society of America in Chicago. After one more year of experience I decided to re-write it and put it on my web site to make this useful information accessible to wider readership. I kept the original photos - especially Goniądz roadsign appealed to readers whose ancestors came from there - but I have added one or two more. Grażyna Rychlik, 10th January 2010.

This is a subject which gets relatively little coverage and many people who are planning to visit Poland rely on travel information about Poland coming from those who visited the country a long time ago (for example in the 70-ies). Poland has been changing really fast over the past 20 years so even 5-10 years old information may be out of date. In my tour manager capacity (last 10 years) I have worked with groups of travelers who brought with them food, band aids and other goods easily available in Poland and they were surprised to see that these products (incuding food!) were available in every shop in town and village. Bearing in mind restrictions on luggage weight kept by air carriers and what you may be possibly wishing to bring back from Poland it is worth rethinking what you really need to take with you so that you don't put yourself in a situation in which you will have to dispose of otherwise useful things because they will be too heavy and/or take too much space in your luggage. Preparation for a genealogy trip to Poland is even less addressed even in more specialized literature and journals. This is a subject which gets relatively little coverage and many people who are planning to visit Poland rely on travel information about Poland coming from those who visited the country a long time ago (for example in the 70-ies). Poland has been changing really fast over the past 20 years so even 5-10 years old information may be out of date. In my tour manager capacity (last 10 years) I have worked with groups of travelers who brought with them food, band aids and other goods easily available in Poland and they were surprised to see that these products (incuding food!) were available in every shop in town and village. Bearing in mind restrictions on luggage weight kept by air carriers and what you may be possibly wishing to bring back from Poland it is worth rethinking what you really need to take with you so that you don't put yourself in a situation in which you will have to dispose of otherwise useful things because they will be too heavy and/or take too much space in your luggage. Preparation for a genealogy trip to Poland is even less addressed even in more specialized literature and journals.

Once you have decided that you are going on an ancestral journey to Poland, it is worth taking a moment to plan it to make sure that you will achieve at least some of your genealogy objectives.

What travel method gives best results?

There are several ways of how family genealogy journey can be organized. I put them in 2 general categories. Let's look at pros and cons of each of these ways.

Organized tour to Poland with hope to take a day off from the program, hire a car and guide and visit ancestral locations (or prearrange such a one day tour).

Sounds easiest but in reality gives the least satisfaction if not none at all. It works at the expense of not participating in the program you have paid for plus you have to additionally pay for it. Additionally, because the tour may not exactly go where your ancestors were from, this may mean a very long day of driving 6-8 hours with little time at the actual ancestral location, being tired, achieving little and being happy but once the emotions go away disappointed that so little was achieved at such high cost.

If little preparation even for such a short expedition is made you may end up in the wrong place (there are lots of villages (and even towns) in Poland with the same name but located in different places and geographically far away).

If you still want to do it on one transatlantic/air ticket better come 3-4 days earlier (or as much earlier as you want to spend on ancestral journeying and research) or stay after the tour and dedicate this time to your private ancestral journey whether self organized or organized with help of a professional ancestral travel company or a private guide.

Private tour self organized or organized by a professional company in the U.S. or with help from a professional genealogist in Poland where genealogy is the main objective (and if time permits or such is your desire you can build into such a program some tourist itinerary like a tour of Warsaw, Kraków, Zakopane etc.) whether you use a hired car with driver or a car hire company (there are many choices of car hire and the prices are not so high any more).

This way of ancestral journeying is highly recommended provided it is well prepared. Regardless of who prepares it at some point in the planning process advice should be sought from or essential information checked with (see 'How to achieve your objectives' section of this article) a professional genealogist in Poland so that you can at least minimize the risk of failure.

Although this way may seem to be more expensive, it can prove to be of the same cost if not lower especially if you travel in a party of 3-4 or more relatives. It is worth asking family members whether they might be interested to undertake such a journey with you. It may turn out that some of them or one of them had such a journey in mind but was afraid to do it on his/her own but would love to do it in the company of others.

What is important to remember is that Poland is a relatively big country (similar in size to the state of New Mexico in the U.S.). The most centrally located city is Warszawa [Warsaw] (it is 190 miles away from Krakow).

As far as international travel goes Warsaw or Kraków will be the most likely cities in which you will be arriving by plane so it is good to work out which one will be best for you. There are more and more direct flights to Poland and especially in the high travel season there are direct connections between New York, Chicago, Toronto and Warsaw every day once a day or even more often and some direct flights between New York, Chicago and Kraków. If direct connection is not good for you, you will be arriving via one of European ports of which Frankfurt or London is most likely.

Travelers arriving from Europe will have many more options to get directly to a large town closest to the ancestral area.

I have worked with family genealogists whose one part of the family came from former Galicia and the other from Wielkopolska/Poznań area or northern Mazovia. There is also a solution to this, you can arrive in Kraków and depart from Warsaw or even Poznań.

It is important to bear all this in mind when planning out a complex itinerary, especially when you have several ancestral locations you want to visit and they are not in the same area. Also when you want to build some tourist program into your ancestral trip to Poland because your ancestral territories maybe hours away from tourist sites.

As far as traveling in Poland is concerned: there are very few fast roads so for simplicity of calculation you can assume that you will be moving at 40-45 miles per hour or less if traveling through small villages or big towns which have no circulars but lots of traffic lights and congested roads. The cheapest gasoline is righ now at $ 1,6 per 1 liter (price depends on the international situation on the oil market and the $ rate and for example in 2008 went up to $ 2,3 per 1 liter).

Setting objectives

Is you trip long planned and desired or is it just a holiday idea because you have been everywhere else so your ancestral country is now next on the list?

Whether you have any expectations at the outset or not it is good to do some planning because this way you can get more out of it and such a trip may turn out to be more rewarding than any other traveling that you have done so far. Also planning process may convert you into a genealogist or at least you will realise that this way you may be able to answer questions you formed long time ago and always wanted answered but somehow you never had the time to do something about it.

So whether you want to achieve this or not it is worth looking at possible objectives - which I am listing below:

- you will be happy to just be in the village your great grandparents / grandparents / parents emigrated from; taking a picture of the roadsign indicating your ancestral village or town and taking it back home to show to other family memembers will make you very happy

- you want to explore everything in the ancestral location where you can find some traces of presence of your ancestors and their relatives (baptismal church, cemetery, village/town, family house)

- you want to attempt at looking for living relatives (you do have - or don't have - something to go on, like old envelopes and letters, old names, addresses etc.), if you start planning early, there will be time to look for all the necessary information at home or check with the relatives what they may possibly have that will be helpful in your research

- you want to do a real research into vital records or other documents which complement the history preserved in the vital records which means that you want to visit archives, local libraries and other institutions which may store useful for the family research information

You may wish to achieve all these objectives or a little bit of each of them or some of them. Until you get to the site you can't be sure what is possible - unless you find people who have roots in the same area as yours, they have been to Poland or done the research and will be able to share the information with you. You can also hire a professional genealogist in Poland to do a pre-research for you. This may seem to add to the cost but may work to your advantage - you will be aware of what is out there and what can be possibly found. Pre-research will gather a lot of information for you. This can also help to plan the trip in time. But of course you may wish to take part in the whole research process - then just plan the trip and come to Poland.

How to achieve you objectives

Best traveling time (season)

There is no formula and each season has its pros and cons. I would suggest traveling to Poland any time between March and September. The main reason is that the daylight will last till 8.00 p.m. (of course in June and July till 9.00 p.m. but there are some other constraints about July). March will be most probably still cold and not welcoming. April may be cold and hot (following a popular Polish proverb kwiecień plecień bo przeplata trochę zimy trochę lata - which simply means that you should not be surprised at winter or summer weather - too hot or very cold even with snow) but the fact that there are still few or no leaves on the trees gives often better visibility of buildings and other objects of interest. It is very important for those who want to take pictures of particular objects.

|

|

Photo (on the left) of the church in Wizna was taken in April. The other photo (Rudka) was taken in June. There are fewer trees by the other church but with leaves on those few trees it was very difficult to take a good picture of the entire church building in Rudka.

May, June and September are the peak of the season and hotel room prices are highest. July and August are holiday months in Poland (school is out) which may mean having limited choice of good and inexpensive accommodation in holiday areas - practically all of the southern Poland which is the ancestral homeland to all those whose ancestors emigrated from Galicia.

There are several dates which should be avoided or partly avoided - you can be in Poland but don't travel between Gdańsk and Warsaw, Warsaw and Kraków and especially Kraków and Zakopane on days starting and ending the so called long weekends which fall around May 1st and May 3rd, on Corpus Christi (which falls always on Thursday) or on August 15th (the feast of the Assumption). There may be no other choice for you, but then be prepared that some parts of the journey may take twice as long as they should,or longer... Also if you are planning to visit Jasna Góra in Częstochowa, bear in mind that the largest pilgrimige on foot to this sanctuary culminates on August 15th. It will be VERY crowded there even a few days before and when visiting then you will not have any other kind of experience but standing in a crowd.

There are several dates which should be avoided or partly avoided - you can be in Poland but don't travel between Gdańsk and Warsaw, Warsaw and Kraków and especially Kraków and Zakopane on days starting and ending the so called long weekends which fall around May 1st and May 3rd, on Corpus Christi (which falls always on Thursday) or on August 15th (the feast of the Assumption). There may be no other choice for you, but then be prepared that some parts of the journey may take twice as long as they should,or longer... Also if you are planning to visit Jasna Góra in Częstochowa, bear in mind that the largest pilgrimige on foot to this sanctuary culminates on August 15th. It will be VERY crowded there even a few days before and when visiting then you will not have any other kind of experience but standing in a crowd.

On the other hand religious festivals present an opportunity to see some old customs like the Corpus Christi procession shown in the picture. For some people it may be more important to see how their ancestors observed religious holidays in the old country then to go through piles of records or visit cemeteries.

Best traveling time for archive research

Most of archives in Poland take a month or so off in either July or August and this cannot be always confirmed when you are buying your air ticket. To be on the safe side it is better to avoid these summer months if archive research is your major objective. And it can be main objective because many records have not been microfilmed by LDS Church so checking the books is the only way to learn the family history.

Best traveling time in the week

This is of course very hard to define partly because it depends on the objectives you want to achieve. My advice would be as follows: if you want to see the interior of a church, Sunday till 1.00 p.m. is always a good time, there will be masses but the church will be open. Practically everywhere there are evening masses every day of the week but in some smaller villages this isn't always the rule. Pretty much the same applies to Orthodox churches in eastern parts of Poland.

Orthodox and Uniate churches in the former Galicia, Lutheran and other Protestant churches again should be best visited on Sunday mornings - they usually have one mass on Sunday.

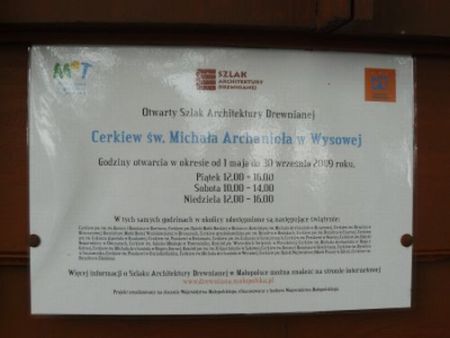

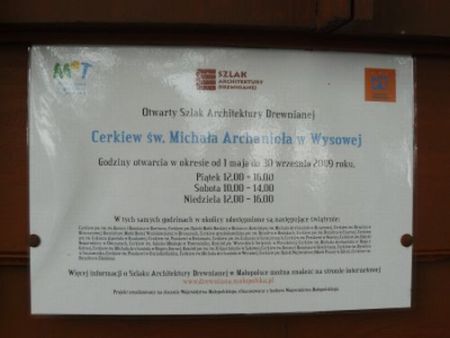

Most of buildings of Uniate churches in the former Galicia (regardsless of who is the current host today) have visiting hours from Friday to Sunday which are often the same for a large area and posted somewhere on church buidlings.

Most of buildings of Uniate churches in the former Galicia (regardsless of who is the current host today) have visiting hours from Friday to Sunday which are often the same for a large area and posted somewhere on church buidlings.

Synagogues which are open for religious services can be visited any time except for Saturdays and religious holidays unless you want to join the service. Synagogue buildings, unless they are museums or libraries (and then their working hours apply), are locked and you may have to ask around in the town or village for a person who is the custodian and has the key.

Every day in the afternoon and Sunday all day is the best time if you want to do some interviews in the villages; on Sunday afternoon people will be definitely at home unless visiting family in the neighborhood.

Research into vital records in parish churches

This is valid only if you want to research the Roman-Catholic records (for all other religions read the information about the archive research). It is not so easy after all. Parish priests in Poland have lots of duties and you will rather not find them during the day at home Monday to Saturday. They do have hours for visitors, which vary, but usually parish offices are open after mass on Sunday or once a week in the evening. Town parish offices have usually long opening hours for visitors. You can try to prearrange such a visit but whether the appointment will be kept depends on what duties the priest will have on the given day. It is good to make such appointments at rather short notice.

Research into vital records in the state archives

This is valid for vital records of all religions (until 1945 civil records were run by religious congregations and this is why in most instances in genealogy research religious divisions apply) represented in Poland. It is very important to determine in which state archive records of religious congregation of interest to you are located. Database of the Polish State Archives may not be up-to-date in some instances. From January 1st, 1999 new administrative division of Poland was introduced which resulted in transfer of some books of vital records to the territorial archives reflecting the current administrative division. This is just a causion. Once you have identified the archive check on the map where it is in comparison to your ancestral locations, sometimes it can be even 100 miles away or so.

Also read the information on the LDS Church site with caution. Data base of microfilms tells you where the records were when they were microfilmed - in case of the state archives it was in 1960s, 1970s and 1980s at the latest. Since then some books of records and copies of microfilms have been transferred (there were 2 changes in administrative division of Poland since 1960s) to different archives and they may be far away from what the LDS Church data base suggests.

It is not unusual that records for the same religious congregation for differfent years will be in two different archives.

When you are buying your tour from a genealogy travel agent or hiring a local guide it is good to give all information on your planned research at the beginning so that the tour plan can be adjusted by checking all these small details in the planning process rather than wait until you are in Poland when rearranging the itinerary may be simply impossible because for example the days with which you can play around in the itinerary are Saturday and Sunday.

Languages

Subject to which part of partitioned Poland your ancestors were from at least working knowledge of different languages is necessary to read books of vital records or other documents.

Just a reminder:

- in the Polish Kingdom the language of state administration (and records) until 1867 was Polish and between 1868-1915 Russian

- in Galicia, the language of Roman-Catholic records was Latin - this is not too bad on the whole because records were held in table format which makes them very easy to read and Latin in some respects is closer to English than Polish (take names of months for one);

in the same Galicia, Jewish books of records were run in Polish

- on territories which were in the Prussian partition or directly in East Prussia the necessary language is German but in the Prussian partition also Latin.

Unless you are fluent in all these languages you have to have some language help. Archive staff will help you but they have no capacity to do the work for you unless you commission a project. Many priests from the parishes which were in the former Polish Kingdom don't know Russian and can't (even though they would like to) help with reading books of records after 1867. Also if you employ a person to help you in your project make sure they will be able to help languagewise. Although Russian is back to grace, there are lots of people who never studied Russian in school and can't read Cyrillic alphabet, they may be great as guides but they will help you little with reading records.

If you are planning research into books of vital records it is good to study examples of translations of records in for example Going Home by Jonathan D. Shea, A.G.

Conclusions

Of course it is unpredictable what your impressions of the country of your ancestors will be. It is also hard to tell what will be in the end most important for you. You may change your objectives after the first meeting, first object found, first relative you talked to but it is important to remember that there is a range of objectives to achieve epecially when you are not getting far on just one. Interviews with local community may be very helpful - villagers may remember where your (sometimes only potential) relatives moved out, where the parish previously was, which cemetery is the oldest, why people were emigrating from that particular area. You may also be lucky to find a local historian in your ancestral area. They rarely speak English but often are known to the community; they are local teachers or retired professionals and they usually with pleasure give up some of their time to talk to you about the old times.This is why it is always good to have a fluent Polish (and English) speaker with you.

This for sure does not exhaust the subject. However, I tried to highlight the areas which must not be neglected when planning a successful ancestral journey to Poland. I hope you will find all these tips useful.

Photos in this article:

View on the Biebrza river

Roadsign indicating the distance (1 km) to Goniądz

Roman-Catholic church in Wizna

Roman-Catholic church in Rudka

Corpus Christi procession in Kołbiel

A sign on the Uniate church in Wysowa

Researching parish books of records somewhere in Galicia

Top of page

Cemetery Research

Cemetery research is an integral part of genealogy research.

Today we have several types of cemeteries in Poland but in the past there were only cemeteries run by religious congregations, cemeteries where soldiers were buried (World War I military victims were the first ones to be buried in such special way) and plague cemeteries.

Cemeteries of particular religious congregations have their unique features, which we should take into account when planning cemetery research. Below I am giving some information on how far back in time we can go with information we can find on gravestones, why at all it is worth researching cemeteries and in which research situations it is a very important research tool.

I concentrate here on the most frequently researched cemeteries. But the list is much longer. It also includes remains of Mennonite cemeteries, several Tartar and Muslim cemeteries, Calvinist cemeteries, Crimean Karaite (in Central Europe known as Karaims) cemeteries, Orthodox cemeteries and so on and so on. I only mention but do not give too much information on all cemeteries located today across borders to the east of the country. Cemeteries of particular religious congregations have their unique features, which we should take into account when planning cemetery research. Below I am giving some information on how far back in time we can go with information we can find on gravestones, why at all it is worth researching cemeteries and in which research situations it is a very important research tool.

I concentrate here on the most frequently researched cemeteries. But the list is much longer. It also includes remains of Mennonite cemeteries, several Tartar and Muslim cemeteries, Calvinist cemeteries, Crimean Karaite (in Central Europe known as Karaims) cemeteries, Orthodox cemeteries and so on and so on. I only mention but do not give too much information on all cemeteries located today across borders to the east of the country.

Territories of historic and present Poland suffered terribly in history. Land, buildings and communities were subjected to terrible acts of violence from devastation to annihilation. Totalitarian regimes (Hitler's and Stalin's) acted as if both people and material objects of the country were objects which could be disposed of without any hesitation to achieve primary objectives on regime leaders' agenda.

Post WWII decisions on the shape of Central Europe were taken without presence of the countries in question. For Poland it resulted in big transfers of people both in the country and across borders, also in unwanted and unasked for territorial changes. Some people could not take it all in any longer and in absence of any kind of counseling took their smaller or bigger private revenges for everything they suffered physically and mentally during and after the war. It all had to take its toll.

Cemeteries are an integral part of community lives and cannot function independently. This integrity was irreversibly broken in many instances. Some cemeteries were also subjected to private revenge.

This is why so many cemeteries in Poland are in such a bad state. Condition of a cemetery is a testimony of the fate of the community, which it served. There was no community, which survived the history of Poland intact.

Roman-Catholic Cemeteries

Unless your family was among the grandest in the country or at least belonged to high nobility you will not be able to find graves older than the end of the 19th century. Famous aristocratic families have their gravestones in prominent locations in the most important churches all over Poland. Funeral portraits, which were a unique and characteristic Polish feature, Unless your family was among the grandest in the country or at least belonged to high nobility you will not be able to find graves older than the end of the 19th century. Famous aristocratic families have their gravestones in prominent locations in the most important churches all over Poland. Funeral portraits, which were a unique and characteristic Polish feature, are still kept in family collections or you can find the best examples of them in the collections of best Polish museums like the National Museum in Warsaw or Wilanów Palace Museum in Warsaw. Some will be simply hanging on walls in some churches. are still kept in family collections or you can find the best examples of them in the collections of best Polish museums like the National Museum in Warsaw or Wilanów Palace Museum in Warsaw. Some will be simply hanging on walls in some churches.

Big cities like Warszawa (Warsaw), Kraków, Poznań, Radom but also Suwałki which was once 5th largest town in Poland and many others founded their cemeteries sometime at the end of the 18th century or early in the 19th century so if you have town roots chances are that you may find family graves going back to the first part of the 19th century (which means that you may be lucky to find graves of the relatives who were born some time in the 18th century). to find graves of the relatives who were born some time in the 18th century).

Photographs in this section come from Tarnów cathedral (graves of Tarnowski brothers) and the exhibition catalogue: Stanisław Leszczyński the king of Poland and the prince of Lorraine. The two funeral portraits depict Bogusław Karczewski (d. 1723) and Joanna Jadwiga Dziembowska (d. 1755).

If you have village roots the tradition to bury people in a cemetery and mark the place with a cross and an inscription of who is buried is simply not that old.

Of course even village cemeteries (and churches) will have old gravestones but they will rather mark burial places of owners of estates, founders of the church etc.

How graves are preserved and how much information you can find depends really on how the family has taken care of them. Some families will tell you where great-great grandparents were buried even though today there is another grave of people unrelated to the family on the same spot. Sometimes there will be mention of those past genrations of relatives on the contemporary graves. They were not buried exactly there but in the cemetery research inscriptions are more important than the actual places where graves once were.

Roman-Catholic cemeteries are rather not indexed. So practically the only method to do the research is to take a walk along all paths of the cemetery and while walking concentrate on not missing what you are looking for (usually we are looking for known family names). It is fine in small locations, and especially if done by 2-3 people it is not too difficult a task. With large cemeteries it can be a big problem. Some large cemeteries will have indexes but not all.

Pictures show two cemeteries in former Galicia, the one on the left in Jordanów and the one on the right in Szalowa.

Jewish Cemeteries

On the territory of the 18th century Poland lived half of the world's Jewry. Borders shifted, size of the territory changed and so the statistics and demography. It is estimated that in preWW2 Poland lived 3,2-3,5 million Jewish people constituting about 10% of the total population. Most of the community lived in towns small to large and even if some people lived in villages they would be buried in community cemeteries in towns.

Jewish community was decimated during WW2. Just over 20 years later remnants of the community were reduced again, in 1968, by practically compulsory emigration from communist Poland. This simply means that after 1945 (and especially after 1968) there were very few Jewish people left in Poland to take care of the Jewish community heritage (including the cemeteries) amassed over the estimated 1000 years of Jewish presence.

In a very simplified way we can divide existing Jewish cemeteries into 3 categories:

- in big cities like Warsaw or Poznań etc. where they are under direct supervision of community authorities which are located in the city; they were not undamaged in history but major parts of them survived in a relatively good condition;

for example the Jewish Cemetery of Warsaw is being indexed so it is possible to search this way for ancestors too for example the Jewish Cemetery of Warsaw is being indexed so it is possible to search this way for ancestors too

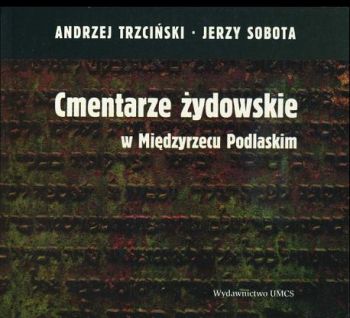

- in smaller towns where cemeteries survived with more or less damage but even if the cemeteries are under supervision of the Jewish community there is no Jewish community as such in this town or even in the area; they are rarely catalogued unless someone becomes interested and he or she is not necessarily Jewish; I am copying cover of the book on Jewish cemeteries of Międzyrzec Podlaski which is a desired kind of publication on all Jewish cemeteries and would be a great help to researchers - it gives the history of the location but what is most important contains a catalogue of graves with photos and inscriptions;

in many places where only crushed parts of few tombstones were found the decision was taken to preserve them in some way - many have been embedded in cemetery walls or walls surrounding synagogues; among these broken pieces we can sometimes find what we are looking for

- cemeteries which were destroyed during WW2 or after the war often because of some construction projects but also because of neglect and lack of community to take care of them; without knowing from another source or finding someone in town who will know how to direct us to the site there is nothing, not even a plaque or stone to mark the site of the cemetery

The oldest Jewish gravestones (5) in Poland are remnants of the medieval Jewish cemetery in Wrocław (Przedmieście Oławskie) and go back to the times between 1203-1345 (matzevah of cantor David, the oldest in Poland, from 1203 is now on display in a museum in Wrocław). Many Jewish cemeteries were created in the 16th century and graves going back to those times can be probably found for example in the cemetery in Lesko but also at other cemeteries in today's Poland or across borders to the east.

It is probably obvious, except for city cemeteries - and it does not apply to many graves - you have to read Hebrew to study inscriptions on graves.

One of the problems with Jewish genealogy is that until the early 19th century (in the Russian partition of Poland until 1822) Jewish people did not have hereditary family names. The family name was derived from the first name of the father but this way every generation in the same family had a different family name. This is an obstacle, which will not allow you to trace ancestry line back in time into the 18th century and earlier even though the graves are there in a traditional way (which is tracing lines back in time using a common hereditary family name). Complex researches can be done to determine the families but it has not been done much. On the other hand you may have information on where your family was from in Poland and simply visit the site and the cemetery there.

Please remember that many cemeteries will close early on Friday and will be closed on major or all religious holidays.

Pictures below were taken at 2 different Jewish cemeteries, from the left: Lesko, Szczebrzeszyn.

Lutheran Cemeteries

Again it is not possible to write about Protestant cemeteries without history of present territory of Poland in mind. Lutheran cemeteries of former East Prussia will be described under Mixed Cemeteries heading.

Lutheran communities lived both in villages and towns. They were mainly German colonists who came to Poland in the second part of the 18th century on invitation of many parties. For example the oldest Lutheran parishes in the Land of Dobrzyń were established - Michałki in 1784 and Lipno in 1793 and so subsequently were the cemeteries founded. Emigration of the German Lutheran families from Polish territories started in the 19th century, many people emigrated when Poland became an independent country in 1918. But the real beginning of an end of normal life for these German Lutheran communities living in Poland for 150 years or so came with the beginning of the World War II. Small communities remain in the same churches until the present time but many people left before the end of the war or just after the war, also later on as part of economic emigration to Germany from communist Poland.

Cemeteries are still there and usually they are indexed by the communities. One can find some old graves but they are also new ones and it is not impossible to find a lead to living relatives despite the history.

Some cemeteries are hard to find. For example when a new church was built in Rypin the community practically transferred there even though Michałki was a seat of the community for many many years. Today it is hard to find the cemetery in Michałki.

Sometimes with luck it is possible to find guidebooks to these cemeteries or graves listings in some local publications - this can be very helpful even when the cemetery is in bad condition and hard to find.

It is possible to find some really old graves on Lutheran and other Protestant cemeteries (it really depends on when these communities established their presence in the country - eventually they were composed not only of foreign settlers but also of some native community members) - of the ancestors born in the 18th century. Some, like for example Warsaw and Częstochowa Lutheran cemeteries, have very good guide books with indexes. Usually there is much more information given in grave inscriptions - like for example occupations. Cemetery offices - if cemetery documentation survives - may also have very interesting information on where in Europe people came from, where and when exactly they were born and so on and so forth. If you are lucky to know where your Lutheran ancestors lived in Poland and the cemetery documentation survives you may be lucky to find a lot of valuable information. Sadly there are not that many cemeteries with surviving documents.

Pictures below were taken at the Lutheran (Evangelical-Augsburg) cemetery in Warsaw. You may be surprised to see an Orthodox grave chapel there. Jan Skwarcow, a rich Russian merchant, struck a deal with the cemetery to be buried there.Orthodox cemetery was pretty new in Warsaw at that time (Skwarcow died in 1850) whereas Lutheran cemetery, established in 1792 was much more prominent a cemetery to be buried at.

Ruthenian/Greek-Orthodox/Uniate Cemeteries (different names but they all mean the same)

These cemeteries can be found in abundance in south-eastern (slightly south-east of Kraków), southern and eastern Poland. Also across the border in Slovakia and Ukraine. Because post-WW2 communist authorities in Poland treated all Ruthenians as members of Ukrainian nationalist movement they were almost all resettled in the so called Akcja Wisła/Operation Vistula far away from their homeland territories. Some chose to live in the Soviet Republic of Ukraine and left Poland. On the other side of the border many Polish people decided to leave their homeland and rather live in communist but independent Poland than in the Soviet Republic of Ukraine. The transfer/resettlement of people in either case replaced about 90% of original populations. This is why the communities were not there to tend to the Greek-Orthodox cemeteries in Poland and Roman-Catholic cemeteries in the Soviet Republic of Ukraine (also of Belarus). Today Greek-Orthodox cemeteries are in pretty good condition but there are always huge empty spaces on them where some older graves once were and are no more. Many of these cemeteries were transferred to Roman-Catholic or communal cemeteries. As communal cemeteries they have old (Greek-Orthodox) sections with often very few remaining graves and new a section with Roman-Catholic graves. Some also have military cemetery sections (around Gorlice, in the Beskid Niski area where a huge battle took place during WWI and later on state military cemeteries were especially designed for all soldiers who perished in that war and battle in that area). they were almost all resettled in the so called Akcja Wisła/Operation Vistula far away from their homeland territories. Some chose to live in the Soviet Republic of Ukraine and left Poland. On the other side of the border many Polish people decided to leave their homeland and rather live in communist but independent Poland than in the Soviet Republic of Ukraine. The transfer/resettlement of people in either case replaced about 90% of original populations. This is why the communities were not there to tend to the Greek-Orthodox cemeteries in Poland and Roman-Catholic cemeteries in the Soviet Republic of Ukraine (also of Belarus). Today Greek-Orthodox cemeteries are in pretty good condition but there are always huge empty spaces on them where some older graves once were and are no more. Many of these cemeteries were transferred to Roman-Catholic or communal cemeteries. As communal cemeteries they have old (Greek-Orthodox) sections with often very few remaining graves and new a section with Roman-Catholic graves. Some also have military cemetery sections (around Gorlice, in the Beskid Niski area where a huge battle took place during WWI and later on state military cemeteries were especially designed for all soldiers who perished in that war and battle in that area).

It is complicated in a way. To understand why a former Greek-Orthodox cemetery looks the way it looks depends on its location in Poland, how big influence the Operation Vistula had, how many people left Poland for Ukraine etc. In the communist times these were all hush hush topics but today for example in Dębno near Leżajsk on the restored Greek-Orthodox section of the cemetery there is a plaque explaining in detail the complicated history of the village. This would be impossible in the 1970s or earlier.

Putting the condition of graves and cemeteries aside you will rather not find graves with inscriptions older than second part of the 19th century. Also please bear in mind that inscriptions are in Ukrainian which means that they are in the Cyrillic alphabet. Contemporary graves will have inscriptions either in Polish or in Ukrainian.

Picture above was taken at the cemetery in Cieplice. Pictures below were taken in Dębno and show the restored part of the cemetery. The whole project was implemented by a local organization with financial help from the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage.The green information board telling the history of Dębno was placed at the cemetery - unfortunately the text is only in Polish.

Communal Cemeteries

They were created after WW2 and mainly in towns (with the exception of mixed cemeteries - please see below). They are not run by any religious communities but by the local authorities. Both religious and non-religious burials are accepted there. Either at the cemetery or somewhere in town (this depends on the size of town and availability of venues in possession of local authorities) you can find Zarząd Cmentarza - cemetery office. My guess is that a lot of these offices have computer data bases but because of the data protection law in Poland you may be asked many questions and even asked to present documents connecting you with the person you are looking for before any information will be given to you.

Mixed Cemeteries officially called Communal Cemeteries

As said above they are under city administration. The difference is that they were originally created in the historic times but today they have different kinds of people buried and graves are from different historic times. A good example of mixed cemeteries are cemeteries in former East Prussia. I will skip fascinating history of the area which I am encouraging readers to look up. As an example let me give the cemetery in Rozogi / Friedrichshof - once a border town between Poland and East Prussia on the Prussian side. Church and cemetery originally belonged to the Lutheran community. The church building was bought by the Roman-Catholic Church in 1970s and so the cemetery now has old Lutheran graves (in most cases remains of them), war graves and contemporary community graves. It also has a lot of today empty but once, probably just after the war, devastated space.

Another example of mixed cemeteries I already described above. They are some former Greek-Orthodox cemeteries. Today in some formerly Ruthenian villages lives predominantly Roman-Catholic community so at cemeteries in these villages you will find old and new graves of people buried in different rites.

All photos in this section come from the cemetery in Rozogi.

War Cemeteries

There are lots of military cemeteries in Poland. The most organized ones are the cemeteries from WWI around Gorlice where a huge battle took place in May 1915. They are all numbered, well signed and there is a lot of literature written and indexing done on them. They are in different conditions. Sometimes they will still have names of soldiers on graves. Practically if your roots are Austrian, German, Russian, Hungarian, Slovak, Czech, Polish and from further southern outskirts of the Austro-Hungarian empire chances are that some of your ancestors - they had to be men in military service - are buried there.

There are also military cemeteries from the times of the Second World War where soldiers of different armies (the Soviet Army, Allied forces) who perished in various circumstances are buried. They are located near places of high military activity and where prisoners of war camps were located. There are lots of military cemeteries in Poland. The most organized ones are the cemeteries from WWI around Gorlice where a huge battle took place in May 1915. They are all numbered, well signed and there is a lot of literature written and indexing done on them. They are in different conditions. Sometimes they will still have names of soldiers on graves. Practically if your roots are Austrian, German, Russian, Hungarian, Slovak, Czech, Polish and from further southern outskirts of the Austro-Hungarian empire chances are that some of your ancestors - they had to be men in military service - are buried there.

There are also military cemeteries from the times of the Second World War where soldiers of different armies (the Soviet Army, Allied forces) who perished in various circumstances are buried. They are located near places of high military activity and where prisoners of war camps were located.

Civilians were rather buried at regular cemeteries unless they died in unusual circumstances. Then in most cases place of burial is unknown.

I don't include victims of mass killings here. Information on war crimes can be found in relevant institutions and literature.

All pictures in this section were taken in 2009. Top photo shows the cemetery in Smerekowiec. At the bottom from the left: Regietów and Ropa. Each cemetery has a number which is posted on a pole on the main road leading to the cemetery and each has a description in Polish and German.

Plague Cemeteries

Plagues were a pest all over the world in the past times - but we know that we are very afraid of development of any kind of uncontained disease now, too. In the old times sometimes all villages or towns disappeared when disease spread. People who were dying of black fever, cholera and other diseases were buried at separate cemeteries and sites of some of them are marked and known until the present time.

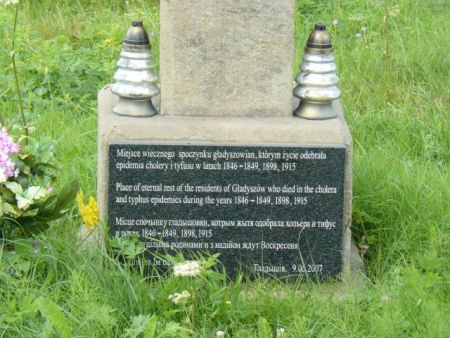

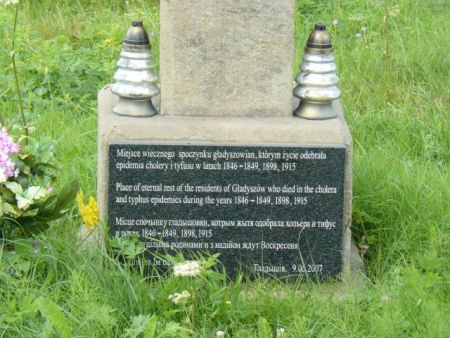

I was really surprised to find this stone which gives a description of the site even in English!

Plague cemeteries are curiosity and rarity. We will not find any names of people buried there but if we have done research into vital records and noticed that several family members or relatives died in the same year it is very likely that they died in an epidemics and so they were buried at those separate cemeteries.

This picture was taken in Gładyszów in 2009. It shows a newly made (2007) plaque put on a monument marking place of burial of the inhabitants of Gładyszów who died in epidemics of typhoid and cholera in 1846-1849, 1898 and 1915. It is interesting that the inscription in this theoretically remote village is in Polish, English and Ukrainian which makes understanding accessible to many travelers.

Why is cemetery research useful and what information can we gather?

First of all I want to divide cemetery visits to two categories.

One is when we want to pay respects to the family members who passed away long time ago and not so long time ago. One is when we want to pay respects to the family members who passed away long time ago and not so long time ago.

In Poland people visit family graves quite often. The tradition is that you light candles and put flowers on graves. Most of foreigners who visit Poland at all times in the year always remark on the Polish cemeteries and as a tour guide I had to make many stops on request for my groups so that travelers to Poland could take pictures of those ornate in flowers, candles and sculptures cemeteries.

The day when everybody visits cemeteries in Poland is 1st November, All Saints' Day. These days, if you happen to be in a big city in Poland on the day, a walk in an old historic cemetery is a must not only for Polish citizens but many foreigners visiting or working in the country. In Warsaw you have to be prepared to get through the crowd to the cemetery gates and once you are at the cemetery you can spend hours walking around.

What is so special about town cemeteries in Poland, especially in the former Russian partition of Poland? The fact that it was practically impossible in the second part of the 19th century to place any monument in town streets without permission of the tsar. It was a very complicated process with many restrictions for Polish people so many sculptors had to adjust to the situation and they showed their talents in design of grave sculptures and composition of grave decorations. This is why many Polish town cemeteries are also sculpture galleries. And this is true for cemeteries of every religious denomination.

Both photographs were taken in Warsaw around 1st November 2009. One shows a stand with decorations at the second largest Roman-Catholic cemetery in Warsaw, Bródno Cemetery; the other was taken at the historic Roman-Catholic cemetery, Powązki Cemetery, the oldest existing cemetery in Warsaw.

Genealogists may visit cemeteries to pay respects to the departed relatives but they can also gather wealth of information. Research visit is however another type of cemetery visit.

Cemetery research is very useful especially when we are looking for:

- in general, dates of birth and death of our relatives; we can find several generations which will be very helpful in tracing family history - for the descendants of the immigrants from Poland it will be helpful to recreate the history of the family who stayed in Poland

- information on family and relatives born within 100 years from the year when we are carrying out the research - access to such information is otherwise limited and guarded by law and relevant local institutions

- information on whether the family is still in the area (it can be done in a different way but if you are in Poland on a research trip and are in the area anyway, cemetery may give you many clues)

- information on whether the family name is still in the area, whether it is rare or quite popular (again, it can be done in many different ways but a quick look at the cemetery immediately answers the question)

- images/photographs of our ancestors - many and these days more and more graves have photographs on them; they will not only tell us what some of our ancestors looked like but sometimes will also show the style of their clothing which may be unique to the particular region or village

Also Jewish cemeteries in big cities (like Warsaw) will have some graves with photographs on them; in principle it is impossible but in practice it was possible; they will be rare but you never know what you can find at a cemetery

Cemetery research is very important when looking for living relatives. If research into records was carried out prior to your trip to Poland then cemetery will tell you who passed away and whose children you will be possibly looking for. Sometimes it is very sad to see that you missed the connecting generation - someone who would personally know your immigrant ancestor - by 2-3 years, sometimes by 10 years. It is rare but still in many villages (and towns - only there they are harder to find immediately) you can meet people in their nineties who knew your family and will be able to tell you something that you did not know about your ancestors.

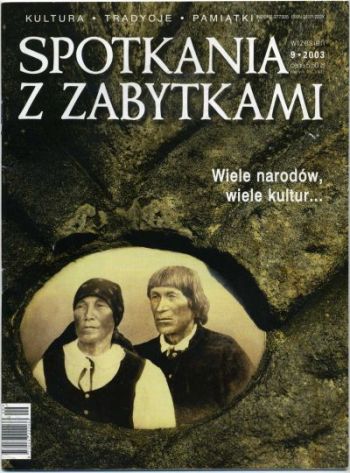

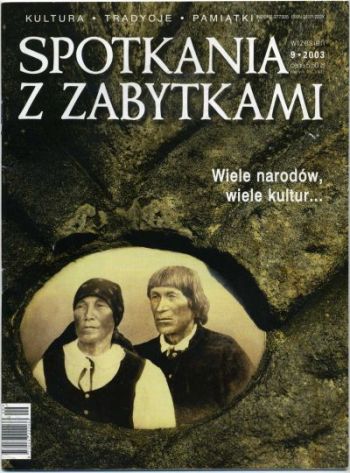

I copied a cover of the monthly Spotkania z Zabytkami from September 2003 issue. It shows the most frequently published (in Poland) grave photo from the Greek-Orthodox cemetery in Uście Gorlickie.

It is worth taking pictures of all graves of relatives and potential relatives. It is also worth taking pictures of the entire body of the grave and separately of the plaque with description. It is also good to make sure that flowers and candles don't cover important parts of text because it may be very difficult to have these pictures done again if you discover at home that there are some faults in the pictures you took.

Different religious traditions have different attitudes towards cemeteries. For some people they are burial places only. For family historians they can be a very useful source of family information including the family photos.

Top of page

|

There are several dates which should be avoided or partly avoided - you can be in Poland but don't travel between Gdańsk and Warsaw, Warsaw and Kraków and especially Kraków and Zakopane on days starting and ending the so called long weekends which fall around May 1st and May 3rd, on Corpus Christi (which falls always on Thursday) or on August 15th (the feast of the Assumption). There may be no other choice for you, but then be prepared that some parts of the journey may take twice as long as they should,or longer... Also if you are planning to visit Jasna Góra in Częstochowa, bear in mind that the largest pilgrimige on foot to this sanctuary culminates on August 15th. It will be VERY crowded there even a few days before and when visiting then you will not have any other kind of experience but standing in a crowd.

There are several dates which should be avoided or partly avoided - you can be in Poland but don't travel between Gdańsk and Warsaw, Warsaw and Kraków and especially Kraków and Zakopane on days starting and ending the so called long weekends which fall around May 1st and May 3rd, on Corpus Christi (which falls always on Thursday) or on August 15th (the feast of the Assumption). There may be no other choice for you, but then be prepared that some parts of the journey may take twice as long as they should,or longer... Also if you are planning to visit Jasna Góra in Częstochowa, bear in mind that the largest pilgrimige on foot to this sanctuary culminates on August 15th. It will be VERY crowded there even a few days before and when visiting then you will not have any other kind of experience but standing in a crowd. Most of buildings of Uniate churches in the former Galicia (regardsless of who is the current host today) have visiting hours from Friday to Sunday which are often the same for a large area and posted somewhere on church buidlings.

Most of buildings of Uniate churches in the former Galicia (regardsless of who is the current host today) have visiting hours from Friday to Sunday which are often the same for a large area and posted somewhere on church buidlings.

One is when we want to pay respects to the family members who passed away long time ago and not so long time ago.

One is when we want to pay respects to the family members who passed away long time ago and not so long time ago.